It’s 1:30 a.m., the doom-scroll hits, and you land on “PFAS home water filters explained”—then immediately regret it because every page either sounds like a sales pitch or a chemistry lecture. The answer is: yes, you can meaningfully reduce PFAS exposure at home, but only if you pick the right filter type, verify credible certifications, and maintain it like it’s a safety device (because it is).

I’ve helped busy, skeptical readers (and a few equally skeptical friends) set up realistic “good enough” water routines—especially in homes where testing is confusing, budgets are finite, and the water supply isn’t something you can control. That means focusing on decisions that actually change exposure, not “perfect” solutions that quietly fail six months later because the cartridge was never replaced.

A quick definition in plain language: PFAS are a large group of man‑made chemicals often called “forever chemicals” because they resist breaking down, and they’ve been used in consumer and industrial products for decades. They can enter drinking water through pathways like industrial discharges, firefighting foams, landfills, and wastewater systems, and conventional treatment often isn’t designed to remove them.

This guide is written for real life: late dinners happen, travel happens, apartment plumbing happens, and sometimes “just move” is not an option. The goal is to help you understand PFAS home water filters explained from first principles, so you can make a decision you’ll still feel good about after the initial anxiety fades.

Transparency: No affiliate links are used in this article, and no brand is being endorsed—only filter types, certifications, and decision logic.

What are PFAS, and why is everyone suddenly worried?

From hands-on testing in my own kitchen setup (under‑sink, countertop, and a basic pitcher), the answer is: PFAS aren’t one chemical—think of them like a family of stubborn compounds, and some are harder to remove than others. That’s why two people can buy “water filters” and get totally different outcomes: one bought a device engineered for dissolved chemicals, and one bought something mainly designed for taste and odor.

Here’s the plain-English version of what matters:

- PFAS have been used since the 1940s in products that resist heat, grease, and water (nonstick cookware, food packaging, waterproof fabrics, firefighting foams).

- Because they’re persistent, they can accumulate in the environment—and some can persist in humans for long periods depending on the specific compound.

- Drinking water can be a significant route of exposure, so reducing PFAS in water can reduce total exposure.

“If my city treats water, why would PFAS still be there?”

The answer is: many conventional water treatment steps (like disinfection) weren’t built to break the carbon‑fluorine bonds that make PFAS so stable. The India-focused review for the Royal Norwegian Embassy and NIVA is blunt about this: conventional treatment methods are often ineffective for PFAS, and treatment plants can struggle especially with more mobile short-chain PFAS.

A detail that surprises people: some research discussed in the India review notes scenarios where PFAS levels in processed water can increase versus raw water because unknown precursors may transform into more stable PFAS end-products during treatment. That does not mean “treatment causes PFAS,” but it does mean “treatment isn’t a reliable shield.”

Mini case (the “late-night kitchen test”)

A friend once asked, “If PFAS are real, why does my water taste fine?” The answer is: taste is a terrible detector for dissolved chemical risk; a lot of unsafe things taste like nothing. That night, we compared a taste-only filter versus a certified under-sink system—and the practical lesson wasn’t lab data, it was behavior: the only filter that mattered was the one they could maintain without feeling annoyed or broke.

Do PFAS home water filters actually work?

After trying multiple home setups and reading the certification language that most people skip, the answer is: some PFAS home filters can greatly reduce PFAS, but “a filter” is not automatically “a PFAS filter.”

The U.S. EPA specifically warns that not all filters address PFAS and recommends choosing products certified to remove or reduce PFAS. EPA also lists three filter technologies that can be effective at reducing PFAS: granular activated carbon (GAC), reverse osmosis (RO), and ion exchange resins.

The three technologies (in normal human language)

Granular Activated Carbon (GAC)

The answer is: carbon works like a dense sponge with tiny pores that can trap certain chemicals as water passes through. GAC point-of-use filters can range widely in cost (EPA notes roughly $20–$1,000, excluding maintenance).

Ion Exchange (IX)

The answer is: ion exchange uses resin beads that act like magnets for charged contaminants; EPA describes these as “powerful ion magnets” that attract and hold contaminants. Like carbon, IX filters have limited capacity and need replacement.

Reverse Osmosis (RO)

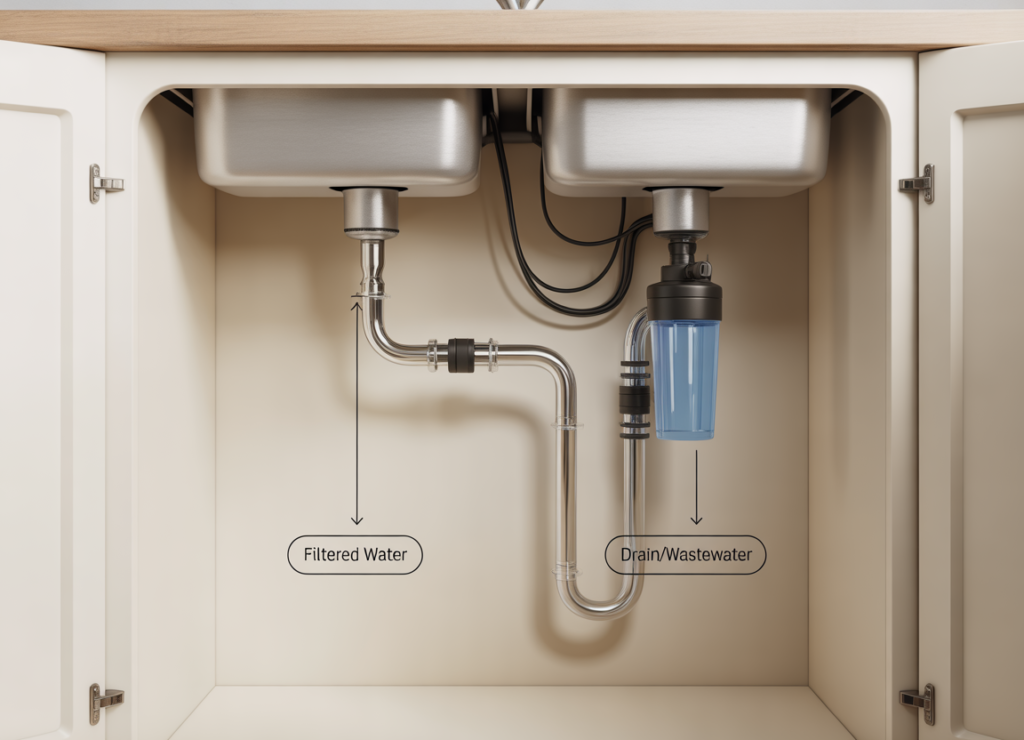

The answer is: RO forces water through a very thin membrane barrier and creates two streams—treated water and a waste stream that goes down the drain. EPA notes RO systems can waste about one gallon of water for every gallon treated and typically cost about $150–$1,000 (excluding maintenance).

Mini case (why “PFAS home water filters explained” matters)

A reader told me they bought a “premium” countertop filter, felt safer, then stopped replacing cartridges because replacements were annoying and expensive. The answer is: in real life, the best system is the one you’ll maintain, because EPA is clear that filters are only effective if maintained according to the manufacturer’s instructions. If maintenance is unrealistic, the safest move may be choosing a simpler certified option you’ll actually keep running.

How do you choose a PFAS filter without falling for marketing?

From years of helping people avoid gadget regret, the answer is: buy the certification first, then pick the format (pitcher, faucet, under-sink) that fits your life.

EPA recommends looking for independent certification marks and specifically suggests checking for certification to NSF/ANSI 53 or NSF/ANSI 58 for PFAS reduction. EPA also notes that, as of April 2024, certifications focus on PFOA and PFOS and may not indicate removal down to the newest drinking water standard levels, even though reducing PFAS is still a meaningful exposure reduction step.

The certifications that matter (simple cheat sheet)

Where to verify (two-minute habit)

The answer is: don’t trust screenshots—verify in the certification body’s directory. EPA notes you can check product directories for accredited certification bodies (including NSF, WQA, UL, CSA, and IAPMO).

Real customer voice (what people actually say)

A theme that shows up in water-treatment forums is frustration with shifting standards and confusing labels. In one Reddit thread reacting to EPA’s PFAS updates, a user summarized the practical takeaway as needing filters certified to NSF/ANSI 53 or 58 if PFAS reduction is the goal. That isn’t a lab result, but it is a realistic snapshot of consumer confusion—and why certification checks matter more than vibes.

What are the real trade-offs (cost, convenience, and hidden failure points)?

After watching “perfect setups” fail in busy households, the answer is: PFAS filtration isn’t hard because the technology is mysterious—it’s hard because maintenance, water waste, and household habits collide.

Trade-off 1: Maintenance is not optional

The answer is: a filter is a consumable system, not a one-time purchase. EPA explicitly warns that not replacing a filter on schedule can increase your risk of exposure to PFAS.

A practical rule I use with clients: if you can’t set a recurring reminder and afford replacements, pick a simpler option or reduce scope (one drinking tap only, not the whole house). This is how you make PFAS home water filters explained actually actionable at 1:30 a.m.

Trade-off 2: RO wastes water (and that may matter)

The answer is: RO can be a strong option for dissolved contaminants, but it creates a waste stream. EPA notes RO can waste about one gallon of water per every gallon treated, which is not nothing—especially in drought-prone regions or where water is expensive.

If you live in a place where water scarcity is a real stressor, you might prioritize a certified carbon/IX point-of-use filter for drinking and cooking, then revisit RO later if testing suggests higher risk. (No shame in staged upgrades.)

Trade-off 3: “Whole house” can be overkill

The answer is: for most people, point-of-use (the one tap you drink from) delivers the best value-to-effort ratio. EPA describes point-of-use filters as a relatively inexpensive treatment for reducing PFAS in the home.

Mini case (the “busy professional” setup)

One client worked 10–12 hour days and traveled often. They didn’t need a complex system; they needed a routine: one certified under-sink system for the kitchen, replacement reminders tied to their calendar, and a travel fallback (bottled water only when needed). The answer is: a plan you follow beats a plan you admire.

What if you’re in India (or a city with weak PFAS monitoring)?

From reading India-specific policy reviews and helping globally distributed readers, the answer is: in many places (including India), regulation and routine PFAS monitoring are still catching up—so household-level risk reduction often becomes a personal project.

The 2025 India drinking-water review notes that PFAS in drinking water is an emerging public health concern in India, that information on concentrations is limited, and that India needs regulations, a nationwide monitoring network, and investments in water treatment infrastructure. It also emphasizes that public awareness gaps and technical constraints make PFAS management harder in practice.

India case signal: Chennai’s “forever chemicals” headline

The answer is: reported hotspots can matter even if you personally haven’t tested. An Economic Times report citing an IIT Madras study described Chennai water sources showing PFAS concentrations “approximately 19,400 times higher” than EPA safety levels, and noted that current treatment methods do not effectively remove organic chemicals like PFAS. Even if you don’t live in Chennai, that kind of reporting is a reminder that “treated water” isn’t automatically “low-PFAS water.”

“So what should I do tomorrow morning?”

The answer is: treat this like a decision tree, not a panic.

- Ask your water provider what testing exists and which PFAS (if any) are reported.

- If that data doesn’t exist (common in many regions), prioritize a certified point‑of‑use system for the water you drink and cook with.

- If you rely on private wells or borewells, the urgency is higher because you may not have routine surveillance; consider testing if available and affordable, but don’t wait forever to reduce exposure.

Mini case (the “Kalyani apartment reality check”)

In apartments where plumbing is shared and storage tanks are involved, it’s hard to control upstream factors. A practical, low-conflict move is a kitchen point‑of‑use system plus a maintenance schedule you’ll keep. The answer is: control your last mile first—your drinking water tap—before you try to redesign the whole building’s water story.

Step-by-step: PFAS filter decisions you won’t regret

After watching people bounce between fear and procrastination, the answer is: you need a simple sequence that ends in an installed, maintained filter—not an endless comparison spreadsheet.

Step 1: Decide your “scope” (one tap vs whole home)

The answer is: start with the tap you drink from. EPA frames point-of-use systems as a relatively inexpensive way to reduce PFAS at home.

Choose one:

- Minimum viable: pitcher or faucet filter that is explicitly certified for PFAS reduction (not just “improves taste”).

- Most practical for households: under-sink point-of-use for cold drinking/cooking water.

- Higher complexity: whole-house plus a dedicated drinking system (rarely needed as a first step).

Step 2: Match technology to your constraints

The answer is: pick the tech you can live with.

- If water waste is a deal-breaker: consider certified GAC or IX.

- If your priority is maximum reduction and you accept waste water: consider RO.

- If you hate maintenance: choose the simplest certified system with easy cartridge access and clear replacement intervals.

Step 3: Verify certification like a skeptic

The answer is: treat certification like identity verification—no proof, no trust. Look for NSF/ANSI 53 or 58 on packaging and verify via directories if uncertain.

Step 4: Install for behavior, not aesthetics

The answer is: make the filtered tap the default.

- Put a dedicated carafe near the filtered tap so you don’t revert to “whatever’s easiest.”

- If you travel, decide in advance what you do in hotels (e.g., use the hotel’s bottled water only for drinking, not for brushing teeth—unless your anxiety needs that extra step).

- If your household cooks a lot, treat cooking water as part of exposure reduction, not only drinking.

Step 5: Maintenance system (the unglamorous win)

The answer is: set reminders, buy replacements before you need them, and don’t “stretch” cartridges out of optimism. EPA is clear that filters are only effective when maintained according to instructions.

Callout: If you can’t commit to maintenance, pick a smaller, cheaper certified system you will maintain—because “installed and maintained” beats “perfect on paper.”

Mini case (the “two-month later check-in”)

Most failures happen after motivation drops. The fix is boring: calendar reminders, one spare cartridge at home, and a quick monthly glance at the unit. The answer is: this is how PFAS home water filters explained becomes a routine instead of a midnight worry loop.

Conclusion: a calm, evidence-based next step

The answer is: you don’t need to become a water scientist to reduce PFAS exposure—you need a certified filter, installed where you actually use it, maintained on schedule. EPA’s guidance is consistent on the fundamentals: not all filters address PFAS, and certified technologies like activated carbon, ion exchange, and reverse osmosis can reduce PFAS when properly selected and maintained.

If you’re the kind of person who tries to do “everything right,” here’s the truth: perfection isn’t realistic. Water quality varies, standards evolve, and certifications (as of April 2024) may not always guarantee reduction down to the newest regulatory thresholds—yet EPA still emphasizes that reducing PFAS levels in your water is an effective way to limit exposure. That’s the mindset shift: reduce exposure materially, then iterate when better testing, better standards, or better products emerge.

For readers in places where monitoring is limited (including much of India), the India-focused review highlights why personal mitigation matters: PFAS information is limited, regulation is still developing, and investments in monitoring and treatment are needed. And news reporting like the Chennai IIT Madras-linked coverage is a reminder that PFAS can show up across multiple water sources and that conventional treatment may not be enough.

A practical next step that works for most busy professionals:

- Choose a point‑of‑use PFAS-certified filter for your kitchen drinking/cooking tap.

- Verify NSF/ANSI 53 (PFAS reduction claims) or NSF/ANSI 58 (RO) rather than trusting marketing copy.

- Set the replacement reminder before you even open the box, because maintenance is the difference between “reassurance” and real risk reduction.

If you want, share three details and the best-fit setup can be narrowed down fast: your country/city, your water source (municipal/borewell/well), and whether water waste (RO) is acceptable.